Loneliness:

I was approached recently by a woman contacted me complaining of overwhelming feelings of loneliness. She felt estranged from her twin sister who had largely cut herself off from this twin as she found her too demanding. They lived just a few streets apart, but had little contact.

The patient felt her loneliness in a visceral way, a welling up in her chest like an intense pain which did not go away for hours. Occasionally she could distract herself from it, but it quickly returned. It was so intense she felt that if she could not resolve it, she might take her own life.

The phantasy twin as a solution to loneliness:

Melanie Klein (1963) wrote of the loneliness engendered by the longing for understanding, a longing to be known, and the common phantasy of having a twin that could integrate split-off projections and find an idealised internal object. She referred to this longing as “essential loneliness”. This loneliness is different from the desperate loneliness I refer to above, as I will explore.

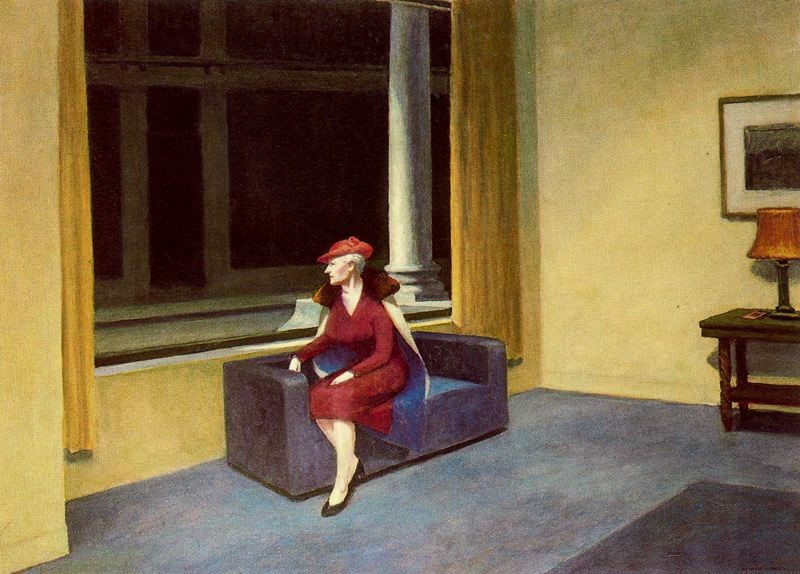

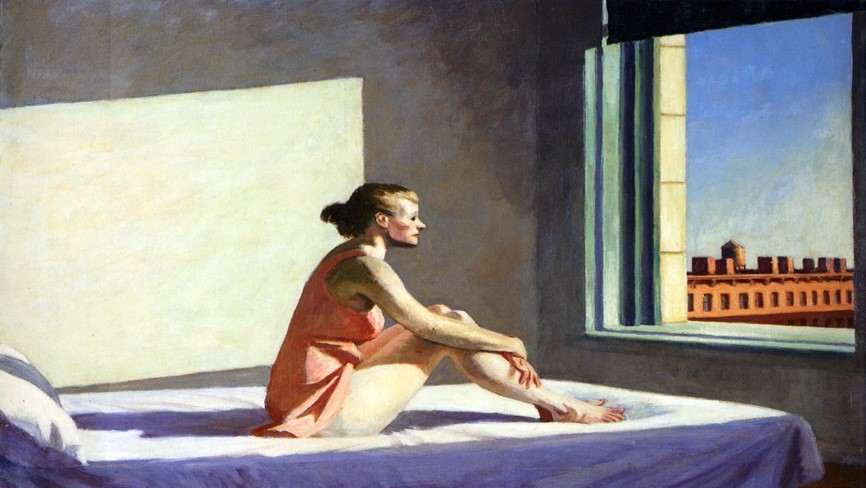

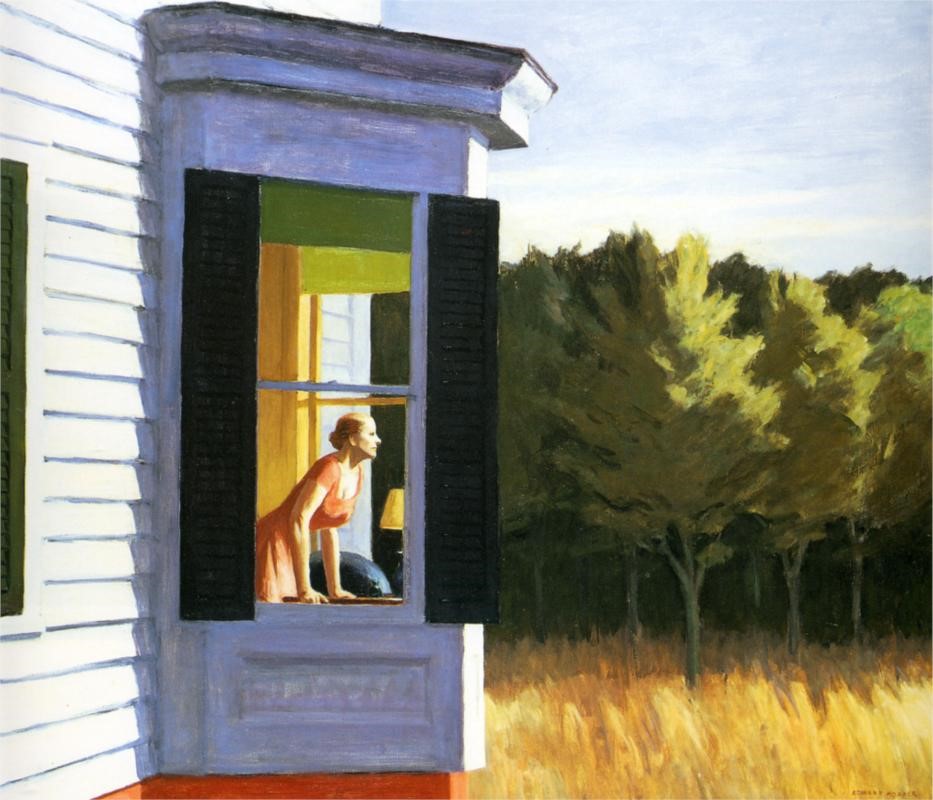

The painter, Edward Hopper wonderfully captured this sense of essential and personal loneliness in his work.

His paintings show figures, whether alone in a room or in a bar with others, who seem isolated, lost in their own worlds, unreachable. They stare out of a window, or into the distance.

Edvard Munch, too, painted people in isolation, even if in a crowd.

In contrast, we see the joy of companionship, and the idealization of the twin relationship in Yinka Shonibar’s work, “Twins riding a butterfly”.

The experience of making live contact, and the fear of invasion of personal space, is graphically captured by Hopper’s arrangements in his studio. He shared a large studio with his wife who was also an artist. But he painted a line across the studio floor to mark out his own space, a line his wife was not allowed to cross except with his permission.

The experience of making live contact, and the fear of invasion of personal space, is graphically captured by Hopper’s arrangements in his studio. He shared a large studio with his wife who was also an artist. But he painted a line across the studio floor to mark out his own space, a line his wife was not allowed to cross except with his permission.

Where does the phantasy twin originate? In earliest infancy, the attuned mother unconsciously understands the non-verbal communications from her infant. The infant feels held in her gaze, as if mother is an extension or twin of himself. The at-oneness with mother waxes and wanes, and it generates a longing to be known, to recapture the perfect soulmate who will understand and love us unconditionally. The longed-for twin-self is a narcissistic object, created by the infant in his own image.

For twins, this phantasy twin of infancy has special relevance. Where there actually is a twin, the task of differentiation of self from mother and the other twin becomes more difficult especially in identifying what belongs to whom. While it is possible for twins to develop into mature adults with a sense of individuality and a capacity for mature relating to others, the task is more difficult than for singletons.

The longing to be known, the difficulty in expressing who we are, is accompanied by a fear of being known, and is a central dynamic as we negotiate relationships, both intimate and more distant. Alongside the longing to be known is a concern with the privacy of the self. We struggle to say in words what can only ever remain unconscious. We offer a representation, a reflection, an intimation of what is brewing in the deeper layers of the self, but it is always an approximation. There is also the unconscious communication that is a central part of any discourse: what we communicate about ourselves and our state of mind through body language, facial expression, and all the other “clues” to unconscious activity that are unwittingly expressed.

Phantasy twins seem to offer perfect at-oneness, without discord or judgement. But the reality of being a twin is, of course, very different. The otherness of the other twin is both a safety net against absorption into another with a loss of self, and at the same time a threat and frustration in relation to the longing to be perfectly known. The thin-skinned relationship between the twins enables the belief (for the twins and those around them) that the twinship will alleviate the essential loneliness of each of them, while the thick emotional skin around the pair will isolate them from a feared intrusion, as well as from external mature containment/understanding.

The idea that twins share perfect understanding with each other is an illusion.

Twins and Developmental frames:

Traditionally we tend to view the creation of a self through a series of developmental frames:

- Containing dyad with mother

- Structural organising triad with mother and father

- Siblings in lateral and peer mode, the family group

- Social group offering a wider societal and ethical circle

For twins, the developmental process is immediately disrupted – they are born as a dyad into a group of three/four (or more).

But perhaps the idea of set sequences does not stand up in reality. I think it is more helpful to consider that we have developmental input from multiple sources all the time, each source having particular characteristics. The various developmental inputs contribute to the most formative experiences of the self and they will evolve around both innate developmental tendencies and the multifaceted nature of external developmental input. Each source of input will have its own value, dynamic, function and tension.

Importantly, I would add to this heady mix the earliest somatic experiences, laying as they do, the foundation of deep, indelible, sensate, proto-mental, non-verbal memories, closely linked with the sense of the self, and inexpressible by ordinary conscious means of communication. As Sigmund Freud: (1926d, p 138) noted, “There is much more continuity between intra-uterine life and earliest experience than the impressive caesura of the act of birth allows us to believe”.

As we encounter the various developmental modalities, we create a sense of otherness and self. We find commonality and difference to help us establish who we are in each setting. Rosine Perelberg noted (2005, in On Narcissism) that the “…encounter with the other is a precondition for the formation of the self.”

By chance, I found an example that illustrates this recently in a newspaper article: “Christopher Knight, the man who walked away from society when he was 20, living in the forests and valleys of Maine for 27 years, said that “solitude increased my perception. But here’s the tricky thing: when I applied my increased perception to myself, I lost my identity. There was no audience, no one to perform for. There was no need to define myself. I became irrelevant.” This obliteration of identity wasn’t, he said, a bad thing. “My desires dropped away. I didn’t long for anything. I didn’t even have a name. To put it romantically, I was completely free.”

(Guardian 28/04/21)

I will now look in more detail at some factors that affect development in twins in particular.

Genes alone do not decide who we become and much research using twin studies has misused or ignored this fact. Furthermore, the environment is never the same for any two individuals, including twins. Environment is not a stable measurable structure. Each person, whether an MZ or DZ twin, sibling, mother, father or live-in grandmother, has their own particular very personal environment within the family. The relationships between each member of the family with every other member is personal, dynamic, and while there are elements of the environment that are shared, their meaning will differ for each member of the family.

Many environmental factors in our lives have a profound effect on the expression of our genes and on our individual development, and this continues throughout our lives. As a result, each twin in a pair is a unique individual with a particular personality and experience of life. But they do share a deep and particular bond.

An understanding of the twinning processes and the early experiences of twins is central to understanding their particular development and how this will impact on all their relationships and in the transference relationship with a psychotherapist.

Twinning dynamics

What is usually the first question an onlooker asks when confronted with two people, particularly babies, of the same age?

“Are the identical?”

The root of this question and our fascination with twins lies both with our idealised phantasy twin of infancy, and the question of personal identity – our own identity. If two babies are born at the same time, more or less, to the same mother and father, into the same household and family, what paths are open to them?

And what paths are open to us?

What if I had made a different decision about …..? What would have happened? Who would I be now?

We believe twins offer us another look at this.

The intrapsychic processes twins must face in their development are not unique to them, but are made more difficult by the fact of the actual existence of another baby right from the start. For twins, it is as if the psychic splitting processes have become embodied: there is another, same age individual who may act as a receptacle for the baby’s projections and this other being is not a mature container able to deal with the projections in a helpful way, in the way a good parent is. Each twin will create a psychic twin, based on the early twinning experiences with both the breast, and with the processes of splitting and projection into the other twin.

Using projection, the other twin will become seen as the embodiment of the phantasy twin, and may be treated as an extension of the self. As a result, there will be both a narcissistic and an object related aspect of each twin relationship, and the predominance of one or the other will determine the health of the individual twins.

As I have already mentioned, particular to twins is an added dimension of developmental experience:

In utero and soon after birth, twins will experience somatic stimuli generated by the other twin – pushing, stroking, kicking, and general movement and sound. While the twins are in a state of sleep in utero until birth, these experiences will create memory traces that are recorded at a proto-mental, preverbal and visceral level. In addition, twins share experiences in growing up together, with the disruption of the usual of dyadic/triadic relationships. They always have to share mother and father, and all of them will have the other twin in mind at all times.

Through all this, twins have to negotiate a personal and private space for each of them within the twin relationship. The twinning processes between all twins intensify the relationship between them. As a result, there will be a distinct tension for each twin as they move towards individuation/developing separateness, with a pull back to an enmeshed twinship that may become intractable and at times toxic/parasitic (Athanassiou, C, 1986).

The nature of projective and introjective identifications between the twins would be affected by the current nature of the twin relationship. In the early stages where there are likely to be a predominance of narcissistic object relations, the identifications between them would be influenced by the unconscious proto-mental experiences and processes, and both the projections and introjections would tend to be of a narcissistic kind – intrusive rather than communicative. As such, the aim would be either to get rid the hated aspects of the self or experience into the other twin, or to appropriate the desirable qualities of the other. Where a twin can more accurately relate to the other twin, the projective and introjective processes would be concerned more with communication between them. We see the valency of discovery as they mature, as opposed to the valency of control in a more immature interaction.

As a result of the twinning processes, the twin relationship is closer and more entangled than other sibling relationships. Splitting and projection between the twins creates a primitive enmeshed matrix. It offers more chance for the narcissistic elements to proliferate from influences both within the twins themselves and in the perception of the self, and from others. These processes will create an indelible core at the heart of the twin relationship, one that will affect all the relationships in which each twin is engaged.

Twinning as a narcissistic state of mind:

It is important to recognise and distinguish two aspects of the twin relationship. There are the ‘special’ aspects of the relationship between twins like the healthy unparalleled closeness and companionship between them. But there are also the more narcissistic elements of the twinship originating from the psychic splitting processes that may result in the idealisation of the twin relationship at the expense of individuation.

Where the idealised phantasy twin is recognised for what it is and is relinquished, the infant twin can mourn its loss and develop towards a companionable type of relationship with its twin, one in which separateness and individuality in the twin pair can be achieved. This process will involve the loss of aspects of the internal psychic twin as well as the projected twin phantasy. It will be experienced as a significant loss, and may at times feel life-threatening. Where this process fails, this may lead to an enmeshed twinship in which each twin feels dependent on the other twin not only for identity, but even for survival. In this sort of enmeshed twinship the twins feel trapped, suffocated in a deadly tangle.

Mourning the lost phantasy twin involves living with the pain of loss in order to do genuine psychological work with it. The loss can then be symbolized through a process of “dreaming”. In contrast to what we usually conceive of as the process for developing a mind for thinking, that we create the apparatus that then enables us to think, Ogden (2005) takes up Bion’s idea that it is the work of dreaming creates the unconscious and conscious mind. Dream work creates the apparatus for thinking. The work of dreaming is to translate the raw sense impressions into unconscious elements of experience that can be linked, and this generates unconscious dream states in which psychological work can be done and understanding gained – a personal narrative of the experience, “truthful archival fictions”.

In contrast, evading the pain of loss leads to a psychotic state of mind where reality is not acknowledged. If the object is not relinquished and mourned, the internal objects remain in a fused state in which “…pathological bonds of love mixed with hate are among the strongest ties that bind internal objects to one another in a state of mutual captivity” (Ogden, 2005, p 43/4), leaving the person unable to “dream” himself into existence as an individual, leaving the twins trapped in a narcissistic bubble.

When a twin loses the other twin, whether through distance, development or death, the experience of loss may leave a devastating sense of loneliness that is visceral, persistent and extreme, as I have described. It is not the loss of the other twin per se that is the precipitant of this powerful loneliness. It is an experience as if a part of the self has been lost. This loss would be the compounded phantasy twin of infancy, the projected aspects of the self which were lodged in the other twin as the embodiment of the phantasy twin, the close narcissistic connections with the other twin, and the loss of a lifelong companion. The experience of such a devastating sense of loss may become encapsulated and will feel persistent, unreachable and leave the remaining twin in a lifelong state of non-being.

With the woman I referred to at the start, I was struck by her rigidity of thinking; ruminating/intrusive thoughts about wanting a partner; a

core pain of loneliness; and not been able to mourn this loss and achieve any resolution. As a result, she is left with a pathological loneliness, rather than what Melanie Klein called essential loneliness.

The narcissistic entanglement in which some twins are caught, is a psychic retreat (Steiner, 1993). It provides apparent shelter from a hostile invasive world, but traps the twins in a bound immature state of mind. Emerging from the psychic retreat will be a painful process. It is vital that twins have space to be individuals within the twin relationship, and neither lose themselves in the twinship, nor deny its importance to them.

The narcissistic aspects of the twin relationship, including the deep sensate bond between them and the idealisation of the twinning processes, will affect the processes of horizontal differentiation that is necessary in order to establish a unique personal identity, and for each to find their place in the world (Mitchell, J 2003). The idealisation of the twin relationship exists internally in each twin and between the twins, as well as in the perceptions of their parents, other siblings and outsiders. Twins may have to work harder for each to establish a rich individual personal identity. Where they do not sufficiently achieve this, this will affect all their relationships in both vertical (parental) and lateral (sibling, peer, marital partner, etc.) dimensions.

Both the nature of twin relationship and our view of it affects our clinical work with twin patients:

Clinical examples

The twin in the transference will be a central aspect of the analysis of twins. The twin transference dynamic is compelling and without analytic attention it may engender transference/counter-transference enactments. The analyst as the transference twin will be subject to the dynamics of that particular twin relationship, both the narcissistic core and the more mature aspects of it active at that point in time.

The pressures that precede a transference/counter-transference enactment are complex. Particular aspects of the twin relationship that are reflected in the transference will create an atmosphere that pre-disposes the analytic pair to enactment.

“In the analysis of a twin there is a central dynamic that pressurises the analyst towards a breach of the analytic setting by an enactment. This dynamic is the fundamentally unbearable quality of the paranoid anxieties and the fear of fragmentation. These qualities arise as the patient emerges from a bound narcissistic state with the analyst-twin, into a state of individual differentiation and a sense of being separate.”

(Lewin V, 2004/14, p136)

The projected transference twin will contain elements of the earliest experiences of the twin relationship (the proto-mental preverbal elements), as well as the earliest twinning relationship with the breast, the phantasy twin. The analyst’s countertransference experience and monitoring of any enactment that has occurred, can provide valuable information about the primitive states of mind otherwise unreachable from verbal associations and dreams, (Joseph, 1985; 1987).

However, the narcissistic twinning created in the transference may be used in the analysis as a refuge against psychic change, in the way that twins use an enmeshed actual twin relationship. This rigid twin structure is maintained by schizoid mechanisms, and emerging from a state of mind governed by such mechanisms creates unbearable pain (Joseph, 1981) and a fear of fragmentation. The narcissistic twin refuge provides a false container offering a fixed sense of identity (Emanuel, 2001) with no possibility for psychic development.

Separation from the psychic twin in the analysis or in the twinship may be experienced as abandonment into the void and generates a terror of non-being (as experienced by Miss D – see below). The refuge that the narcissistic twinship offers is precarious. On the one hand it leaves the individual in a state of constant fear of breakdown (Rosenfeld, 1987) because of its rigidity and instability. On the other, it protects the analytic twins – the patient and the analyst as transference twin – from the terror of facing uncontained experiences of a psychotic intensity (Segal and Britton, 1981).

For enmeshed twins bound in a narcissistic relationship, the functions of true containment will not have been adequately internalised and are therefore not available for use in translating and dealing with new experiences. Instead, the narcissistic inter-twin projective identification will lead each twin to an experience in which projections are stripped of meaning rather than processed and made suitable for thinking. As a result, each twin will re-introject from the other twin an experience of “nameless dread”, rather than one of fear made tolerable by containment (Bion, 1962a: p309). Only the reparative capacity of the internalised parents and their creative intercourse can transform nameless dread into an experience that is tolerable (Meltzer, 1968) and can become understanding and insight. The analyst fulfils this role by using his capacity for reverie and thinking. Where he instead enacts the twin transference, he does so at the primitive levels of the inter-twin relationship and in so doing sacrifices his capacity for containment at that time

Clinical material:

As Sweet

“It’s all because we’re so alike –

Twin souls, we two.

We smile at the expression, yes,

And know it’s true.

I told the shrink. He gave our love

A different name.

But he can call it what he likes –

It’s still the same.

I long to see you, hear your voice,

My narcissistic object choice.”

Wendy Cope, 1992: 9.

I will discuss some aspects of my work with Mr P to demonstrate the changing nature of the transference twin, and the insight this offers into the effects that being a twin had on Mr Ps’ development. A more comprehensive account can be found in my book, The Twin in the Transference, 2004/14.

Mr P is a middle-aged MZ twin. Before he came to see me, he had suffered what appeared to be a psychotic episode following the ending of a romantic relationship. He had become anxious and disorientated, and was in a rather grandiose and hallucinatory state of mind. At the start of treatment this acute state had passed and he recognised that he needed psychotherapeutic help: his state of mind was still very fragile.

Mr P had been married for many years, but his relationship with his wife was problematic. Throughout the marriage Mr P had had a series of affairs. His wife was aware of these extra-marital relationships and although she was greatly distressed by them, Mr P and his wife nevertheless remained inseparable. For both partners, the marriage was like a troubled twinship in which neither could enjoy being either alone or together, and from which neither could escape. Mr P had ended his latest affair because he felt he could no longer tolerate being torn between his mistress and his family. Later his mistress became involved with another man whom she subsequently married

It seems that Mr P had formed an eroticised twin relationship with his mistress. His situation was that he had a cold unrewarding twinship with his wife and an eroticised twinship with his mistress. The breakdown of this structure precipitated his psychotic state of mind. Losing his mistress-twin was experienced as losing a part of himself and a devastating loss of self – a taster of transference issues to come.

Mr P told me his ‘birth story’: he and his twin were born “interlocked”. Mother was told only when she went into labour that she was giving birth to twins. They were delivered by Caesarean section. Mr P was the weaker twin and had had to be resuscitated. He believed his that his twin brother had strangled him in utero, and that after birth he had been neglected, “left for dead”, while all the attention went to his twin. Mr P thought that mother had always favoured his twin and he felt greatly aggrieved about this. He felt he had been cheated of his birthright as the primary place in his mother’s attention: his twin was the bigger, stronger, and more dominant of the pair. Like Jacob and Esau, this twinship was constructed around murderous rivalry.

The crushed-twin/tyrannical-twin transference

In the early period of the treatment, Mr P, was at times involved in a rather delusional system. He believed he was a secret descendent of royalty, and at another time, that he was a champion athlete. This sense of being special manifested itself in my consulting room. He not only filled up all the space with a dominating presence, but in various ways he managed to get me to organise my consulting room to his liking. He persuaded me to reduce the lighting in the room (a counter-transference enactment as I colluded with his belief that he needed special treatment because he was so fragile). At the beginning of each session, he created a seductive atmosphere, taking off his jacket, tie and watch, letting go of any formal attire, as if he were visiting a lover. He noted and commented on what I wore, to try and get me to wear what he liked (as he explained at a later time). He would then begin a hard-edged, flat recital of his activities or ideas, getting more and more worked up about his grievances, until he was shouting in an angry and dominating way for most of the session.

At this time Mr P rarely mentioned his twin. However, he created a transference twin to keep me informed about his current experience of being a twin. He talked and shouted at me relentlessly to push me into a corner like a crushed twin-baby, a twin not noticed, a twin “left for dead”. Meanwhile, he identified with his beefy twin brother and occupied all the space, giving him pride of place. His clinging, abrasive, intrusive voice came at me from all sides, emasculating and controlling me. He stripped my interpretations of meaning by quickly taking them up and intellectualising about them, and by rating my interpretations (“thank you, that’s a good interpretation”) followed by a sterile examination of it. He started each session with his own analysis of the previous session. Throughout this period, he found it intolerable not to understand something before I did, and he fiercely competed with me.

It seemed that Mr P had no sense of my actual presence in the consulting room other than as his creation. As a transference object, I was to be a cold, un-giving, unsupportive, hate-filled twin who wanted to push away the beefy bullying twin to gain some space for myself. He would go through the motions of analytic work with me, bringing lots of material including dreams, but it seemed that the only way to make contact with him or to enter into his private tormented world was as a transference twin. He experienced my interpretations as intrusive and threatening and as an indication not only of my separateness from him, but also of my wish to dominate him.

Mr P reported a dream that illustrated this frame of mind:

He and his twin sat in the public gallery at the House of Commons. His twin was shouting at the members, interrupting the procedures, and getting involved in the debates. His twin was eventually arrested by the police. As they were taking him away, Mr P pleaded with them to release his twin brother.

Mr P felt disappointed that he could not immediately interpret his dream himself. I suggested that the shouting and debating twin was Mr P, here, observing my analytic work (the productive parents/MPs at work) and trying to prevent any thinking from taking place. He viewed my interpretations as the police trying to stop him being so disruptive. He was afraid of exposing a smaller vulnerable twin-self. Instead, an angry, shouting, bullying twin got in the way so that the other needy twin couldn’t tell me what he had come to say.

While I think this interpretation was correct, and Mr P agreed with it, it seemed to carry no meaning for him. He had no idea of my being able to offer him anything other than restrictions to his freedom and a depriving twin relationship. We seemed to be trapped in a limiting and unrewarding twinship in the transference relationship, as Mr P continued with his angry complaints and his self-analysis.

The angry tyrannical-twin was counter-balanced by the crushed-twin, and both were active in the twin transference relationship with me. The confusion of ego boundaries between twins exists not only between the actual twins, but it is also represented in the internal psychic twinship. In psychoanalytic work the transference twin might represent any of a number of aspects of either twin. It was clear that Mr P identified with both sides of the above twin balance. Thus, shortly before a break, Mr P demanded to be seen at a weekend, like an infant who could not tolerate any separation, the weak twin who was supposedly about to be “left for dead”. He was incensed at my refusal to see him, and demanded that I explain to him why I would not accede to his wishes. He found it intolerable that I did not answer his questions in the way he expected me to, and became more and more insistent, creating a tyranny in his relationship with me. While he believed he was a weak needy twin who could not survive without additional sustenance, he enacted a tyrannical twin, hiding his neediness and blocking out the help for which the needy twin cried.

However, around this time the twin transference began to change.

The eroticised-mistress-twin transference

Mr P began to behave in a manic, excited way. He engaged in athletics, which involved him in a considerable amount of training and physical activity. He became more aware of his physical appearance and he dieted and bought new clothes, all accomplished with a great deal of preening. He felt he could not successfully compete with a working twin-me, so he resorted to attempted seduction. His relationship with me became increasingly eroticised and although it was apparent from the start of the work that he regarded me as his new mistress, this now became a florid pre-occupation for him. He brought me flowers and gifts, sent me apparently appreciative cards, agreed with my interpretations of his eroticisation of me, and remained untouched by them.

I had become the eroticised mistress-twin in the transference. As became evident later, the eroticised mistress-twin was based on the eroticisation of the maternal relationship in an attempt to seduce mother to love him as her primary child. Likewise, the cold wife-twin transference was linked with a mother who was not sufficiently available for Mr P and who was perceived as giving all the attention to his beefy brother.

In this omnipotent state of mind, Mr P bound himself to me as an idealised love object. This protected him from painful and difficult feelings, like the terror he had experienced before coming to see me, a fear of falling apart, of disintegrating. What had become apparent was that Mr P’s functioning at this time was based on another narcissistic internal organisation of the twinship. As with the tyrannical twin, he used this eroticisation to prevent the needy twin from emerging.

I found I had to search for the pain behind the erotic phantasies and activities he brought to the analysis, rather than experience feeling either repelled or seduced by him.

Meltzer (1974) refers to the development of a particularly ‘sticky’ erotic transference that is based on narcissism. He suggests that the eroticisation fastens itself onto individual qualities of the analyst, arousing counter-transference interference in the analyst’s capacity to investigate. Only insistence on the analytic method, exploring the infantile nature of the desires and feelings and the masturbatory nature of the excitement felt in the consulting room, will eventually reveal the narcissistic organisation.

Gradually Mr P began to relinquish his idealised eroticised object. The movement out of the thick-skinned psychic twin capsule felt terrifying, but was a necessary step to help him develop a capacity for processing primitive experiences and developing a structure for thinking. His twinning with me in its various guises was part of the process in discovering himself as an individual, but it also created great strains in the analytic work.

The fracture of self with movement out of a narcissistic twinship:

Bateman (1998) noted: “Enactment is particularly prevalent in thick- and thin-skinned narcissistic patients at the point of transition from one narcissistic state to another, just when interpretation becomes therapeutically effective.” At this time, both the patient and the analyst may experience unthinkable anxiety that has a quality of incomprehensibility to both patient and analyst (Joseph, 1981). This anxiety may lead the analyst to collude with the patient to cover up and avoid the analysis of the narcissistic twin transference relationship in the hope of avoiding separation and the terror of fragmentation.

We saw how Mr P tried to avoid emerging from the apparent safety of his psychic twinship with me into an individual sense of self. Material from another patient demonstrates the expression of terror involved in such a massive psychic move.

Descent into the void of fragmentation

I had seen Miss D for several years through various stages of analytic engagement including having been experienced by her as an “identical” twin”. Issues that arose involved, for example: we were wearing we the same skirt? At times she was insistent I knew exactly what she was thinking. By the time I will now describe, we had done a lot of work and Miss D was beginning to be able to tolerate difference and separateness not only from me, but also from her twin sister. This was met with both relief and fear – relief at being separate from her very ill twin sister, but fear of what it meant to be a person in her own right. She had been an unexpected baby, and was very ill after birth. She was not named for 6 weeks, and was always regarded as her twin sister’s shadow.

I had had to move consulting rooms for a period of time, and the sessions I will describe took place in the new rooms. I had taken care to maintain as much continuity as I could, taking all my own consulting room furniture, plants, pictures and rugs to the new room, which was, however, in a different part of London. Another major difference was that my desk and computer were in a “study-corner” of the consulting room, whereas they had previously been located in a room private to me, not seen by my patients.

When I went to meet Miss D in the waiting room, I found her standing with her back glued to the wall, facing the window, staring at a picture on the wall next to the window. She looked terrified. As she walked into the consulting room, she became extremely disturbed by the presence of the computer. In an earlier publication (Lewin 1994) I explored how Miss D had associated a TV monitor with her mirroring ‘identical’ twin. In her current state of mind, it seemed to her that her twin was actually present in the room. She said she felt compelled to sit at the desk in front of the computer, but she resisted doing so.

However, she remained staring at my computer for some time. She looked fearfully around the room and complained about the walls having ears. She said she could not sit with her back to the window (the position that the chair was in) because she felt she had to see who was there, and especially to keep the computer in view. She spent the session sitting on the floor, against the side of the couch, facing the window. She said she felt trapped as she had been in a traumatic childhood incident. She recalled that as a child when her mother was absent over an extended period, she had hidden in rooms behind a chair (as she was doing now). At that time people had come in and out of the room, unaware of her presence while she was able to see them, watch them.

Over the next few sessions, in a continuing “psychotic” state of mind, Miss D relived the pain and confusion of what she experienced as a rupture from her twin – her actual twin, her psychic twin, and her twin-analyst – and the abandonment by her mother in its many forms, from birth and through her life. In both the transference relationship and in my own lack of clear understanding at that time, Miss D experienced me as an absent mother and as a lost ‘identical’ twin, who had abandoned her to her lonely pain and un-thinkable thoughts and feelings. She walked around the consulting room, unable to sit in the chair or lie on the couch. She was extremely agitated and in a fragmented state of mind. She spoke about her psychotic twin sister whom she believed to be very mad and beyond help. I suggested that she was afraid that I would find her as un-helpable as her twin, and that there would be no hope for continuing analytic work, no hope for her to find a containing mother-analyst who could help her become herself.

I was quite taken aback by the change in Miss D. It was evident that she felt assailed by terrifying and unbearable anxieties of the kind associated with fragmentation, falling into a void, nameless dread. She had entered a psychotic mad-twin state of mind in the new consulting room (although by all accounts she continued to function adequately outside).

I was later able to understand with greater clarity the significance of what Miss D was experiencing at the point of separation from a psychic twin in a narcissistic twinship, a time of great vulnerability.

Early in the treatment, Miss D was in a narcissistic twin state of mind that she used to protect herself and her ‘identical’ phantasy twin from external interference. She experienced my interventions as a sadistic attack on the twinship. As she became more able to tolerate them, she began to distinguish me as a separate person, at that stage a ‘non-identical’ twin. She found she could tolerate the sense of difference and space for being. With each movement out of the narcissistic capsule, her anxieties mounted. Miss D had started to separate from a twin who had for a long time provided her with an identity within the twinship, and whom she had regarded as a physical embodiment of herself.

The dramatic change in Miss D represented a psychic move away from a thick-skinned narcissistic twin refuge at a time when she was beginning to be ready to tolerate emerging as an individual within her own right. In emerging from the destructive narcissistic twin bond, she now encountered new emotional territory without the security of her own adequate individual psychic skin. But as already described these giant psychic changes generate intense anxiety at the experience of the unknown, a void. Miss D experienced uncontained anxieties of a psychotic kind linked with fragmentation and the loss of a sense of self as she relinquished her ‘identical’ psychic twin identity. In this thin-skinned state, she had difficulty in distinguishing inner and outer realities.

However, unlike her twin sister, she was later able to recover her fragile sense of self as she re-established her relationship with me as an analyst-mother who could help her develop an apparatus for thinking and processing her experiences in a way in which she could develop a personal narrative, a sense of self, could dream herself into being. Gradually she began to recover her ego functions within her sessions and it became evident that important psychic development had occurred. As she developed a more reliable individual psychic skin, she felt free of the imprisoning destructive narcissistic twinship and could become her own person while also recognising her twin sister without eliminating her.

It is important to recognise that the analytic work with twins is not just about the understanding of the actual twin relationship, but that central to the work will be the psychic twin that is an internal bound object and which will manifest as an enduring pressure in the transference to the analyst.

My work with twin pairs illustrates the various states of development in twin relationships, from very enmeshed on the one hand, to those where both the twinship and the individuality of the twin pair was acknowledged and valued. As I have described at length, there will be many factors contributing to the nature of each twin relationship. All these factors will be active in the twin relationship and the relationship of twins with others, including the analytic pair.

References:

Athanassiou, C. (1986) “A study of the vicissitudes of identification in twins.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 67:329-334

Bateman, A .W. (1998) “Thick- and Thin-skinned organisations and enactment in borderline and narcissistic disorders.” International Journal Psycho-Analysis, 79:13-25

Bion, W. R. (1962a) “The Psycho-Analytic Study of Thinking.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 43:306-310

Birksted-Breen, D. (1996) “Phallus, penis and mental space.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 77:649-657

Brenman Pick 1985 (1985). Working Through in the Countertransference, International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 66:157-166

Britton, R. (1998) Belief and Imagination. Explorations in Psychoanalysis. Routledge: London and New York.

Cope, W. (1992) Serious Concerns. Faber and Faber, London

Durrell L (1957) Justine. Alexandria Quartet

Emanuel R. (2001) “A-void – an exploration of defences against sensing nothingness.” International Journal o Psychoanalysis, 82: 1069-1084

Feldman, M. (1997) “Projective identification: the analyst’s involvement.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 78:227-241

Freud S (1926d): Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety SE 20, 77-178, London. Hogarth Press1959,

Joseph, B. (1978) “Different types of anxiety and their handling in the analytic situation.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 59: 223-227.

Joseph, B. (1981) “Towards the experiencing of psychic pain.” in Psychic Equilibrium and Psychic Change. Selected papers of Betty Joseph. Ed. M.Feldman and E.BottSpillius Tavistock/Routledge: London and New York (1989). Pp. 88-97.

Joseph, B. (1985) “Transference: the total situation.” International Journal Psycho-Analysis, 66:447-454

Joseph, B. (1987) “Projective identification: some clinical aspects.” in Psychic equilibrium and Psychic Change. Selected Papers of Betty Joseph. Ed M. Feldman and E. Bott Spillius, Tavistock/Routledge: London and New York. (1989) pp.168-180.

Kingsolver B (2009) The Lacuna

Klein, M. (1963). “On the sense of loneliness.” in Envy and Gratitude and Other Works. pp. 300-313. The Hogarth press, London, 1980.

Lewin V. (2004,) The Twin in the Transference. Whurr Books, London and Philadelphia (2nd Edition printed by Karnac Books, London, 2014)

Meltzer, D. (1968) “Terror, persecution, dread—a dissection of paranoid anxieties.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 49:396-400

Meltzer, D. (1974) “Narcissistic foundation of the erotic transference.” Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 10:311-316

Motion A (2013) Interview at Burgh House London NW3

Ogden T (2005) This Art of Psychoanalysis. Dreaming Indreamt Dreams and Interrupted Cries. Routledge, UK

Perelberg, R (2005). “On Narcissism” in Freud. A Modern Reader, 72 – 90, Whurr Publishers, London

Rosenfeld, H. (1987) Impasse and Interpretation. Tavistock: London and New York

Segal, H. and Britton, R. (1981) “Interpretation and primitive psychic processes: A Kleinian view.” Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 1:267-277

Steiner, J. (1993) Psychic Retreats. Pathological Organisations in Psychotic, Neurotic and Borderline Patients. Routledge: London and New York